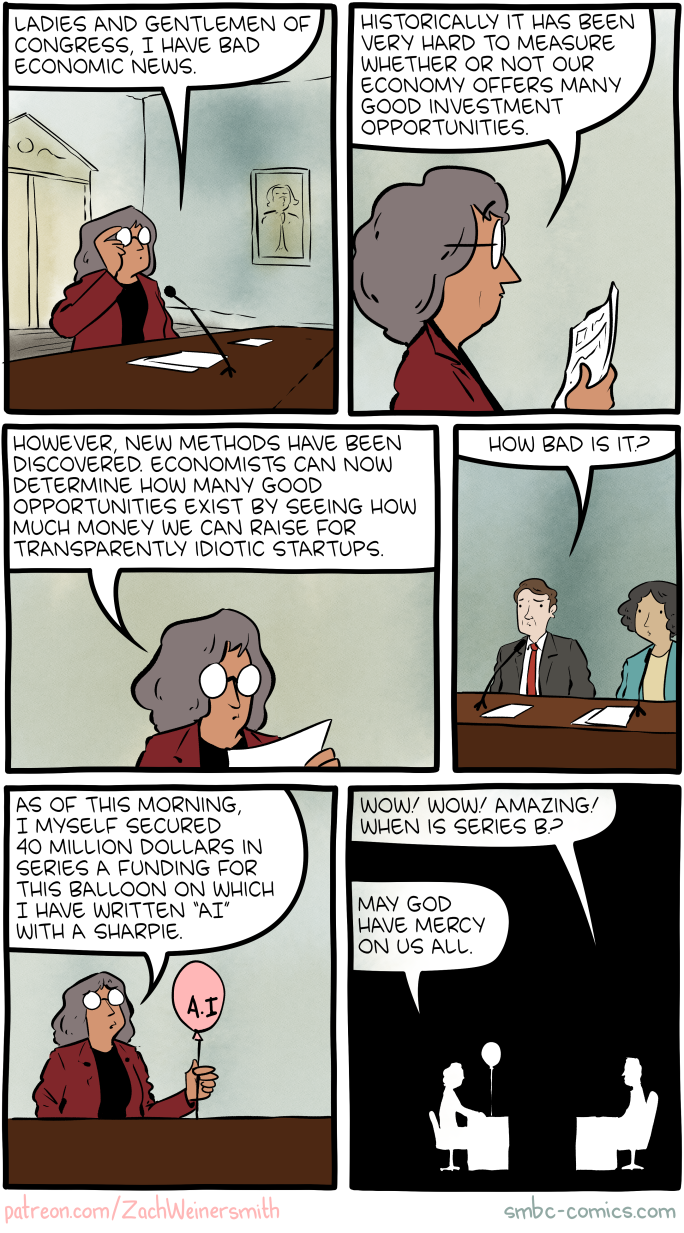

A week and a half ago, Goldman Sachs put out a 31-page-report (titled "Gen AI: Too Much Spend, Too Little Benefit?”) that includes some of the most damning literature on generative AI I've ever seen. And yes, that sound you hear is the slow deflation of the bubble I've been warning you about since March.

The report covers AI's productivity benefits (which Goldman remarks are likely limited), AI's returns (which are likely to be significantly more limited than anticipated), and AI's power demands (which are likely so significant that utility companies will have to spend nearly 40% more in the next three years to keep up with the demand from hyperscalers like Google and Microsoft).

This report is so significant because Goldman Sachs, like any investment bank, does not care about anyone's feelings unless doing so is profitable. It will gladly hype anything if it thinks it'll make a buck. Back in May, it was claimed that AI (not just generative AI) was "showing very positive signs of eventually boosting GDP and productivity," even though said report buried within it constant reminders that AI had yet to impact productivity growth, and states that only about 5% of companies report using generative AI in regular production.

For Goldman to suddenly turn on the AI movement suggests that it’s extremely anxious about the future of generative AI, with almost everybody agreeing on one core point: that the longer this tech takes to make people money, the more money it's going to need to make.

The report includes an interview with economist Daron Acemoglu of MIT (page 4), an Institute Professor who published a paper back in May called "The Simple Macroeconomics of AI" that argued that "the upside to US productivity and, consequently, GDP growth from generative AI will likely prove much more limited than many forecasters expect." A month has only made Acemoglu more pessimistic, declaring that "truly transformative changes won't happen quickly and few – if any – will likely occur within the next 10 years," and that generative AI's ability to affect global productivity is low because "many of the tasks that humans currently perform...are multi-faceted and require real-world interaction, which AI won't be able to materially improve anytime soon."

What makes this interview – and really, this paper — so remarkable is how thoroughly and aggressively it attacks every bit of marketing collateral the AI movement has. Acemoglu specifically questions the belief that AI models will simply get more powerful as we throw more data and GPU capacity at them, and specifically ask a question: what does it mean to "double AI's capabilities"? How does that actually make something like, say, a customer service rep better?

And this is a specific problem with the AI fantasists' spiel. They heavily rely on the idea that not only will these large language models (LLMs) get more powerful, but that getting more powerful will somehow grant it the power to do...something. As Acemoglu says, "what does it mean to double AI's capabilities?"

No, really, what does "more" actually mean? While one might argue that it'll mean faster generative processes, there really is no barometer for what "better" looks like, and perhaps that's why ChatGPT, Claude and other LLMs have yet to take a leap beyond being able to generate stuff. Anthropic's Claude LLM might be "best-in-class," but that only means that it's faster and more accurate, which is cool but not the future or revolutionary or even necessarily good.

I should add that these are the questions I – and other people writing about AI – should've been asking the whole time. Generative AI generates outputs based on text-based inputs and requests, requests that can be equally specific and intricate, yet the answer is always, as obvious as it sounds, generated fresh, meaning that there is no actual "knowledge" or, indeed, "intelligence" operating in any part of the process. As a result, it's easy to see how this gets better, but far, far harder – if not impossible – to see how generative AI leads any further than where we're already at.

How does GPT – a transformer-based model that generates answers probabilistically (as in what the next part of the generation is most likely to be the correct one) based entirely on training data – do anything more than generate paragraphs of occasionally-accurate text? How do any of these models even differentiate when most of them are trained on the same training data that they're already running out of?

The training data crisis is one that doesn’t get enough attention, but it’s sufficiently dire that it has the potential to halt (or dramatically slow) any AI development in the near future. As one paper, published in the journal Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, found, in order to achieve a linear improvement in model performance, you need an exponentially large amount of data.

Or, put another way, each additional step becomes increasingly (and exponentially) more expensive to take. This infers a steep financial cost — not merely in just obtaining the data, but also the compute required to process it — with Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei saying that the AI models currently in development will cost as much as $1bn to train, and within three years we may see models that cost as much as “ten or a hundred billion” dollars, or roughly three times the GDP of Estonia.

Acemoglu doubts that LLMs can become superintelligent, and that even his most conservative estimates of productivity gains "may turn out to be too large if AI models prove less successful in improving upon more complex tasks." And I think that's really the root of the problem.

All of this excitement, every second of breathless hype has been built on this idea that the artificial intelligence industry – led by generative AI – will somehow revolutionize everything from robotics to the supply chain, despite the fact that generative AI is not actually going to solve these problems because it isn't built to do so.

While Acemoglu has some positive things to say — for example, that AI models could be trained to help scientists conceive of and test new materials (which happened last year) — his general verdict is quite harsh: that using generative AI and "too much automation too soon could create bottlenecks and other problems for firms that no longer have the flexibility and trouble-shooting capabilities that human capital provides." In essence, replacing humans with AI might break everything if you're one of those bosses that doesn't actually know what the fuck it is they're talking about.

The report also includes a palette-cleanser for the quirked-up AI hype fiend on page 6, where Goldman Sachs' Joseph Briggs argues that generative AI will "likely lead to significant economic upside" based — and I shit you not — entirely on the idea that AI will replace workers in some jobs and then allow them to get jobs in other fields. Briggs also argues that "the full automation of AI exposed tasks that are likely to occur over a longer horizon could generate significant cost savings," which assumes that generative AI (or AI itself) will actually replace these tasks.

I should also add that unlike every other interview in the report, Briggs continually mixes up AI and generative AI, and at one point suggests that "recent generative AI advances" are "foreshadowing the emergence of a "superintelligence."

I included this part of the report because sometimes — very rarely — I get somebody suggesting I'm not considering both sides. The reason I don't generally include both sides of this argument is that the AI hype side generally makes arguments based on the assumption that things will happen, such as a transformer model that probabilistically generates the next part of a sentence or a picture will somehow gain sentience.

Francois Chollet — an AI researcher at Google — recently argued that LLMs can't lead to AGI, explaining (in detail) that models like GPT are simply not capable of the kind of reasoning and theorizing that makes a human brain work. Chollet also notes that even models specifically built to complete the tasks of the Abstraction & Reasoning Corpus (a benchmark test for AI skills and true "intelligence") are only doing so because they've been fed millions of datapoints of people solving the test, which is kind of like measuring somebody's IQ based on them studying really hard to complete an IQ test, except even dumber.

The reason I'm suddenly bringing up superintelligences — or AGI (artificial general intelligence) — is because throughout every defense of generative AI is a deliberate attempt to get around the problem that generative AI doesn't really automate many tasks. While it's good at generating answers or creating things based on a request, there's no real interaction with the task, or the person giving it the task, or consideration of what the task needs at all — just the abstraction of "thing said" to "output generated."

Tasks like taking someone's order and relaying it to the kitchen at a fast food restaurant might seem elementary to most people (I won't write easy, working in fast food sucks), but it isn't for an AI model that generates answers without really understanding the meaning of any of the words. Last year, Wendy's announced that it would integrate its generative "FreshAI" ordering system into some restaurants, and a few weeks ago it was revealed that the system requires human intervention on 14% of the orders.On Reddit, one user noted that Wendy's AI regularly required three attempts to get it to understand them, and would cut you off if you weren't speaking fast enough.

White Castle, which implemented a similar system in partnership with Samsung and SoundHound, fared little better, with 10% of orders requiring human intervention. Last month, McDonald’s discontinued its own AI ordering system — which it built with IBM and deployed to more than 100 restaurants — likely because it just wasn’t very good, with one customer rang up for literally hundreds of chicken nuggets. However, to be clear, McDonald’s system wasn’t based on generative AI.

If nothing else, this illustrates the disconnect between those building AI systems, and how much (or, rather, how little) they understand the jobs they wish to eliminate. A little humility goes a long way.

Another thing to note is that, on top of generative AI cocking up these orders, Wendy's still requires human beings to make the goddamn food. Despite all of this hype, all of this media attention, all of this incredible investment, the supposed "innovations" don't even seem capable of replacing the jobs that they're meant to — not that I think they should, just that I'm tired of being told that this future is inevitable.

The reality is that generative AI isn't good at replacing jobs, but commoditizing distinct acts of labor, and, in the process, the early creative jobs that help people build portfolios to advance in their industries.

The freelancers having their livelihoods replaced by bosses using generative AI aren't being "replaced" so much as they're being shown how little respect many bosses have for their craft, or for the customer it allegedly serves. Copy editors and concept artists provide far-more-valuable work than any generative AI can, yet an economy dominated by managers who don't appreciate (or participate in) labor means that these jobs are under assault from LLMs pumping out stuff that all looks and sounds the same to the point that copywriters are now being paid to help them sound more human.

One of the fundamental misunderstandings of the bosses replacing these workers with generative AI is that you are not just asking for a thing, but outsourcing the risk and responsibility. When I hire an artist to make a logo, my expectation is that they'll listen to me, then add their own flair, then we'll go back and forth with drafts until we have something I like. I'm paying them not just for their time, their years learning their craft and the output itself, but so that the ultimate burden of production is not my own, and their experience means that they can adapt to circumstances that I might not have thought of. These are not things that you can train in a dataset, because they're derived from experiences inside and outside of the creative process.

While one can "teach" a generative AI what a billion images look like, AI does not get hand cramps, or a call at 8PM saying that it "needs it to pop more." It does not have moods, nor can it infer them from written or visual media, because human emotions are extremely weird, as are our moods, our bodies, and our general existences. I realize all of this is a little flowery, but even the most mediocre copy ever written is, on some level, a collection of experiences. And fully replacing any creative is so very unlikely if you're doing so based on copying a million pieces of someone else's homework.

The most fascinating part of the report (page 10) is an interview with Jim Covello, Goldman Sachs' Head of Global Equity Research. Covello isn't a name you'll have heard unless you are, for whatever reason, a big semiconductor-head, but he's consistently been on the right side of history, named as the top semiconductor analyst by II Research for years, successfully catching the downturn in fundamentals in multiple major chip firms far before others did.

And Jim, in no uncertain terms, thinks that the generative AI bubble is full of shit.

Covello believes that the combined expenditure of all parts of the generative AI boom — data centers, utilities and applications — will cost a trillion dollars in the next several years alone, and asks one very simple question: "what trillion dollar problem will AI solve?" He notes that "replacing low-wage jobs with tremendously costly technology is basically the polar opposite of the prior technology transitions [he's] witnessed in the last thirty years."

One particular myth Covello dispels is comparing generative AI "to the early days of the internet," noting that "even in its infancy, the internet was a low-cost technology solution that enabled e-commerce to replace costly incumbent solutions," and that "AI technology is exceptionally expensive, and to justify those costs, the technology must be able to solve complex problems, which it isn't designed to do."

Covello also dismisses the suggestion that tech starts off expensive and gets cheaper over time as "revisionist history," and that "the tech world is too complacent in the assumption that AI costs will decline substantially over time." He specifically notes that the only reason that Moore's law was capable of enabling smaller, faster cheaper chips was because competitors like AMD forced Intel (and other companies to compete) — a thing that doesn't really seem to be happening with Nvidia, which has a near-stranglehold on the GPUs required to handle generative AI.

While there are companies making GPUs aimed at the AI market (especially in China, where US trade restrictions prevent local companies from buying high-powered cards like the A100 for fears they’ll be diverted to the military), they're not doing so at the same scale, and Covello notes that "the market is too complacent about the certainty of cost declines."

He also notes that the costs are so high that even if they were to come down, they'd have to do so dramatically, and that the comparison to the early days of the internet (where businesses often relied on $64,000 servers from Sun Microsystems and there was no AWS, Linode, or Azure) "pales in comparison" to the costs of AI, and that's even without including the replacement of the power grid, a necessity to keep this boom going.

I could probably write up Covello's entire interview, because it's nasty. Covello adds that the common adage that people didn't think smartphones would be big was false. He sat through hundreds of presentations in the early 2000s, many of them including roadmaps that accurately fit how smartphones rolled out, and that no such roadmap (or killer app) for AI has been found.

He notes that big tech companies now have no choice but to engage in the AI arms race given the hype (which will continue the trend of massive spending), and he believes that there are "low odds of AI-related revenue expansion," in part because he doesn't believe that generative AI will make workers smarter, just more capable of finding better information faster, and that any advantages that generative AI gives you can be "arbitraged away" because the tech can be used everywhere, and thus you can't, as a company, raise prices.

In plain English: generative AI isn't making any money for anybody because it doesn't actually make companies that use it any extra money. Efficiency is useful, but it is not company-defining. He also adds that hyperscalers like Google and Microsoft will "also garner incremental revenue" from AI — not the huge returns they’re perhaps counting on, given their vast AI-related expenditure over the past two years.

This is damning for many reasons, chief of which is that the biggest thing that artificial intelligence is meant to do is be smart, and make you smarter. Being able to access information faster might make you better at your job, but that's efficiency rather than allowing you to do something new. Generative AI isn't creating new jobs, it isn't creating new ways to do your job, and it isn't making anybody any money — and the path to boosting revenues is unclear.

Covello ends with one important and brutal note: that the more time that passes without significant AI applications, the more challenging "the AI story will become," with corporate profitability likely floating this bubble as long as it takes for the tech industry to hit a more difficult economic period.

He also adds his own prediction — "investor enthusiasm may begin to fade" If "important use cases don't start to become more apparent in the next 12-18 months."

I think he's being optimistic.

Hi there. Did you know that I also do a podcast called Better Offline? If not, please immediately download it on your podcast app. Follow the show. Download every episode. Share with your friends, and demand they do the same.

While I won't recount the rest of the report, one theme brought up repeatedly is the idea that America's power grid is literally not ready for generative AI. In an interview former Microsoft VP of Energy Brian Janous (page 15), the report details numerous nightmarish problems that the growth of generative AI is causing to the power grid, such as:

- Hyperscalers like Microsoft, Amazon and Google have increased their power demands from a few hundred megawatts in the early 2010s to a few gigawatts by 2030, enough to power multiple American cities.

- The centralization of data center operations for multiple big tech companies in Northern Virginia may potentially require a doubling of grid capacity over the next decade.

- Utilities have not experienced a period of load growth — as in a significant increase in power draw — in nearly 20 years, which is a problem because power infrastructure is slow to build and involves onerous permitting and bureaucratic measures to make sure it's done properly.

- The total capacity of power projects waiting to connect to the grid grew 30% in the last year and wait times are 40-70 months.

- Expanding the grid is "no easy or quick task," and that Mark Zuckerberg said that these power constraints are the biggest thing in the way of AI, which is... sort of true.

In essence, on top of generative AI not having any killer apps, not meaningfully increasing productivity or GDP, not generating any revenue, not creating new jobs or massively changing existing industries, it also requires America to totally rebuild its power grid, which Janous regrettably adds the US has kind of forgotten how to do.

Perhaps Sam Altman's energy breakthrough could be these fucking AI companies being made to pay for new power infrastructure.

The reason I so agonizingly picked apart this report is that if Goldman Sachs is saying this, things are very, very bad. It also directly attacks the specific hype-tactics of AI fanatics — the sense that generative AI will create new jobs (it hasn't in 18 months), the sense that costs will come down (they're haven’t, and there doesn't seem to be a path to them doing so in a way that matters), and that there's incredible demand for these products (there isn't, and there's no path to it existing).

Even Goldman Sachs, when describing the efficiency benefits of AI, added that while it was able to create an AI that updated historical data in its company models more quickly than doing so manually, it cost six times as much to do so.

The remaining defense is also one of the most annoying — that OpenAI has something we don't know about. A big, sexy, secret technology that will eternally break the bones of every hater.

Yet, I have a counterpoint: no it doesn't.

Seriously, Mira Murati, CTO of OpenAI, said a few weeks ago that the models it has in its labs are not much more advanced than those that are publicly-available.

That's my answer to all of this. There is no magic trick. There is no secret thing that Sam Altman is going to reveal to us in a few months that makes me eat crow, or some magical tool that Microsoft or Google "pops out that makes all of this worth it.

There isn't. I'm telling you there isn't.

Generative AI, as I said back in March, is peaking, if it hasn't already peaked. It cannot do much more than it is currently doing, other than doing more of it faster with some new inputs. It isn’t getting much more efficient. Sequoia hype-man David Cahn gleefully mentioned in a recent blog that Nvidia's B100 will "have 2.5x better performance for only 25% more cost," which doesn't mean a goddamn thing, because generative AI isn't going to gain sentience or intelligence and consciousness because it's able to run faster.

Generative AI is not going to become AGI, nor will it become the kind of artificial intelligence you've seen in science fiction. Ultra-smart assistants like Jarvis from Iron Man would require a form of consciousness that no technology currently — or may ever — have — which is the ability to both process and understand information flawlessly and make decisions based on experience, which, if I haven't been clear enough, are all entirely distinct things.

Generative AI at best processes information when it trains on data, but at no point does it "learn" or "understand," because everything it's doing is based on ingesting training data and developing answers based on a mathematical sense or probability rather than any appreciation or comprehension of the material itself. LLMs are entirely different pieces of technology to that of "an artificial intelligence" in the sense that the AI bubble is hyping, and it's disgraceful that the AI industry has taken so much money and attention with such a flagrant, offensive lie.

The jobs market isn't going to change because of generative AI, because generative AI can't actually do many jobs, and it's mediocre at the few things that it's capable of doing. While it's a useful efficiency tool, said efficiency is based off of a technology that is extremely expensive, and I believe that at some point AI companies like Anthropic and OpenAI will have to increase prices — or begin to collapse under the weight of a technology that has no path to profitability.

If there were some secret way that this would all get fixed, wouldn't Microsoft, or Meta, or Google, or Amazon — whose CEO of AWS compared the generative AI hype to the Dotcom bubble in February — have taken advantage of it? And why am I hearing that OpenAI is already trying to raise another multi-billion dollar round after raising an indeterminate amount at an $80 billion valuation in February? Isn't its annualized revenue $3.4 billion? Why does it need more money?

I'll give you an educated guess: because whatever they — and other generative AI hucksters — have today is obviously, painfully not the future. Generative AI is not the future, but a regurgitation of the past, a useful-yet-not-groundbreaking way to quickly generate "new" data from old that costs far too much to make the compute and energy demands worth it. Google grew its emissions by 48% in the last five years chasing a technology that made its search engine even worse than it already is, with little to show for it.

It's genuinely remarkable how many people have been won over by this remarkable con — this unscrupulous manipulation of capital markets, the media and brainless executives disconnected from production — all thanks to a tech industry that's disconnected itself from building useful technology.

I've been asked a few times what I think will burst this bubble, and I maintain that part of the collapse will be investor dissent, punishing one of the major providers (Microsoft or Google, most likely) for a massive investment in an industry that produces little actual revenue. However, I think the collapse will be a succession of bad events — like Figma pausing its new AI feature after it immediately plagiarized Apple's weather app, likely as a result of training data that included it — crested by one large one, such as a major AI company like chatbot company Character.ai (which raised $150m in funding, and The Information claims might sell to one of the big tech companies) collapsing under the weight of an unsustainable business model built on unprofitable tech.

Perhaps it's Cognition AI, the company that raised $175 million at a $2 billion valuation in April to make an "AI software engineer" that was so good that it had to fake a demo of it completing a software development project on Upwork.

Basically, there's going to be a moment that spooks a venture capital firm into pushing one of its startups to sell, or the sudden, unexpected yet very obvious collapse of a major player. For OpenAI and Anthropic, there really is no path to profitability — only one that includes burning further billions of dollars in the hope that they discover something, anything that might be truly innovative or indicative of the future, rather than further iterations of generative AI, which at best is an extremely expensive new way to process data.

I see no situation where OpenAI and Anthropic continue to iterate on Large Language Models in perpetuity, as at some point Microsoft, Amazon and Google decide (or are forced to decide) that cloud compute welfare isn't a business model. Without a real, tangible breakthrough — one that would require them to leave the world of LLMs entirely, in my opinion — it's unclear how generative AI companies can survive.

Generative AI is locked in the Red Queen's Race, burning money to make money in an attempt to prove that they one day will make more money, despite there being no clear path to doing so.

I feel a little crazy every time I write one of these pieces, because it's patently ridiculous. Generative AI is unprofitable, unsustainable, and fundamentally limited in what it can do thanks to the fact that it's probabilistically generating an answer. It's been eighteen months since this bubble inflated, and since then very little has actually happened involving technology doing new stuff, just an iterative exploration of the very clear limits of what an AI model that generates answers can produce, with the answer being "something that is, at times, sort of good."

It's obvious. It's well-documented. Generative AI costs far too much, isn't getting cheaper, uses too much power, and doesn't do enough to justify its existence. There are no killer apps, and no killer apps on the horizon. And there are no answers.

I don't know why more people aren't saying this as loudly as they can. I understand that big tech desperately needs this to be the next hypergrowth market as they haven't got any others, but pursuing this quasi-useful environmental disaster-causing cloud efficiency boondoggle will send shockwaves through the industry.

It's all a disgraceful waste.

While FlexPosts are more useful than paint, bollards anchored in concrete are a hard "no" to any motor vehicles trying to enter restricted spaces.

Fuck FlexPosts. There, I said it, on behalf of both cyclists and aggressive truck drivers…

While FlexPosts are more useful than paint, bollards anchored in concrete are a hard "no" to any motor vehicles trying to enter restricted spaces.

Fuck FlexPosts. There, I said it, on behalf of both cyclists and aggressive truck drivers…